Tech, Freedom, & the Modern Laborer

Tech, Freedom, & the Modern Laborer

Methods of emotional exploitation & obfuscation driving the modern tech industry—from gig contractors to management.

“Choice is an illusion created between those with power and those without.”

— The Merovingian (yes, that french guy from The Matrix)

I’ve worked at just about every level of a Startup™ over the past decade. I’ve been the courier moving packages around for Uber, I’ve been a freelance designer, I’ve been a full-time project manager, and even (unfortunately) a way-too-young founder with raised investment. I’ve seen a whole lot of cool stuff and way, way, way more terrible stuff throughout all of it. While technology and digitalization are indeed the economy of the future, it’s actually a very dim future for laborers. The modern Entrepreneur™ and Creator™ economy has operated as one of the most successful con jobs of the wealthy to trick laborers into believing they are gaining autonomy in an elite-dominated economy. Wealthy investors gamble on startups and hire freelance creators without real concern for the fallout of failures, expecting the majority of companies they fund to fail in the first two years (percentage is constantly debated, ranging from 60-90%). And yet, despite this clear instability, the public currently seems to take it as a given that going into “tech” is the smartest financial/career move—and maybe it is, comparative to the rest of the economy.

But these jobs are completely unsustainable, from top-level all the way down to gig-hiring. Their entire existence relies on the affective & emotional connection of laborers to the concept of economic & personal freedom. And the fuel that drives their production are byproducts of exploiting this false conception of personal choice & the possibilities of “bootstrapping.” The idea that people can work whenever, wherever, with Unlimited Paid Time Off™. The concept of coworkers being like “family” and deserving of unconditional attention. The intimate personal investment developed by calling any aesthetic jobs “creative projects.” And the constant publicizing of apparently everyday startup-founder success stories. This freedom, and the economic progress people have been sold on, is a farce—and without regulation it is on track to create a truly hellish future of employment for the global laborer.

Unsustainable by design, the modern laborer exists somewhere between human & machine. They are a workforce reproduced by exploitation—diverted from solidarity by classist rhetoric & illusions of free choice.

My Background

To give a quick overview of the background I’m speaking from: I co-founded a funded startup when I was 20 and learned a ton before burning out the last of the Runway™ and shutting down. I proceeded to work with a bunch of companies as a product designer, manager, “owner,” and VP. Prior to all this I was a bike messenger for about three years in the Uber Rush™ program, starting from its first few weeks as a pilot tester. I’ve worked as an official “employee” as well as a contractor and online gig platform worker. Across all these jobs, one certain thread was a feeling of constant emotional-psychological manipulation—from outside and from within.

But before I start ripping things apart, I really cannot stress this enough: I am not anti-tech. I believe technology work is critical for economic growth. What I am opposed to are the economic practices and models that Tech™ currently operates in. Due to a vested interest in maintaining the status quo, which has been artfully rebranded as edgy & fresh when it is just run-of-the-mill exploitive capitalism, one is quickly labeled as some sort of socialist luddite when they criticize the systems in which technology-centered businesses operate.¹ I do believe tech drives the future of the global economy, but tech and the tech-economy are not one and the same. I also would like to make it clear that I do not pity so many of those in the tech world, because they occupy far higher paid positions than the vast majority of the planet’s occupants (or so some of them do)—but their exploitation sets the standard for how those at “lower” levels are treated. When those in management internalize exploitive methods, it is easy for them to then execute them on those with less power in economic structures (almost like how those in the military are taught “torture resistance techniques” in order to make them more amenable to torturing others). We have to treat these as larger labor issues that reproduce themselves starting from the top-down, but aim to make solutions that first prioritize those most disadvantaged. Both rideshare drivers and startup workers are exploited to spend most of the hours in their days laboring, but drivers can’t even afford rent while tech employees live comfortably. And that similarity between them is the very force that drives their disconnect.

In this piece I hope to critique my experiences and the work of modern researchers using feminist & marxist scholarship. Hopefully this will prove useful in digging past the syntactical obfuscations of the modern “tech industry”—leading us closer to to the core of current tech-sphere labor struggles.

False Economy

First off, we need to clearly differentiate between big-tech and the majority of startups (the ones you’ve never heard of that somehow so many people work for). While these two markets overlap in so many ways, grouping them into one “tech” label only does big tech a favor—big tech gets to look like a growing, inevitable economic progression, and startups get to embody a fantasy of being as powerful & successful as their overlords. Those who work at tech giants like Google, Facebook, & Amazon (and many financial-consultancy tech departments) lock down incredibly high salaries and stable futures brought about by monopoly security, while startups compete to get invested in and bought out by these upper technocrats so they can join their successful clubhouse.

Startups™ are basically legal gambling for the hyper-rich. They recreate the same overall economic issues we have in America within the tech world itself.² Under the guise of benevolently making space for new wealth, wealthy investors toss tiny fractions of their wealth into small teams of young people as a means to multiply their wealth without labor-contribution. When any of their “investments” (which, given how much ownership they can take, can sometimes practically become their property) end up with high valuations, or more often, get sucked up by monopolies, they win and can start again. And the beauty of it is that so many of these investors also have stakes in monopoly companies, making it incredibly hard for them to not make money in this process. The smartest economic move for them is actually to intentionally avoid competition to these monopolies, because an acquisition allows them to simultaneously collect their percentage of the acquisition payment, while watching their monopoly rise in valuation.

And on top of all of this, when startups do “succeed” in carving out their own market space without acquisition, they so often do so without ever making a profit, or even posting constant losses, like Uber. Even Amazon only started to barely post regular profits a few years ago. But this isn’t because they’re so well-distributing the revenue to employees, it’s because they have so much investment banking on their future supremacy that they can maintain practices that would be impossibly unsustainable without venture capital. Uber’s entire model is based around eliminating human drivers for a fleet of completely autonomous vehicles—that is such a giant if and yet money pours into that company while they treat employees as sub-humans.

An illuminating answer from a Quora thread regarding how much equity founders should receive.

And what reproduces the labor needed to continually create more and more startups & products to move this wealthy-always-win economy? In my opinion, a large part of it simply cultural perception. I’m referring to parents to telling their children that “tech is where all the jobs are,” without also understanding that in reality most of these new tech workers will be looking for a new contract job every six months to a year while remaining on their parents’ healthcare. And those brought into seemingly “legitimate” startups like WeWork will end up suddenly out of work at the mercy of exploitative con men, with no roadmap to future financial stability besides gambling on the next company—is that really the “futuristic” new employment we’re looking for? There seems to be a confusion generated between “exciting freedom" and “instability” that the industry thrives on. They use tactics like doling out tiny fractions of percents of equity to encourage people to balance this risk, almost bringing them in on a taste of this higher level gambling on success—except the employee doesn’t have 9 other companies they’re betting on. Titles like “Product Owner” create a false sense of true ownership, in which one’s apparently devotion to “live & breath the product” equates to maybe 0.1% ownership of a company, which they will only vest into after, usually, four years time (if the company even makes it that far). Maintaining the exciting, instant-wealth, cool Startup™ image acts as a critical tool of reproducing labor and value for the larger spheres of monopoly tech. There is a vested interest in the image of the overall economy and narrative of “bootstrapping” that tech maintains in order to create new pools of acquirable companies and therefore steadily increasing value.

So with this context, I want to focus on the primary methods through which this economy, from gig to management, works to so effectively extract as much labor as possible from its workers once it has snared them.

“Like a Family” and Unlimited Paid Time Off™

On multiple occasions I have been told that a company I’m entering is “like a family”—and this is probably my #1 red-flag. The work “family” is a method for driving unconditional co-dependence in exchange for a feeling of belonging and familiarity in a workforce.³ It roots in industries like nursing homes and domestic labor and works as an effective tool for extracting free labor labor and reducing ability to criticize labor conditions. It’s especially helpful for upper management, who can cultivate an image of parental-mentor status in order to be given more leeway in mistreating or pushing laborers past their contractual obligations. I’ve seen this “family” sympathy used to delay pay (which I’ve had to settle via the courts), to push for weekend work, and to promote employees coercing their co-workers into extra labor using mob mentality. This sort of collective mentality is pushed by “open-plan-offices” that promote a destruction of privacy and individualism and create further surveillance amongst workers—without even improving tangible productivity. These narratives of trust and love are pradoxicaly used alongside eerily sociopathic management strategies for manipulating the workforce that sound more like someone editing their Sims family than talking to their parent or sibling.

This familiarity works in tandem with the brilliantly deceptive Unlimited Paid Time Off™ (PTO), in which employees are told they may take any time off as needed “as long as their work gets done.”⁴ The beauty in this is that the worker then feels their hours are up to their own control, making them feel as if they’ve been given an incredible deal where they can autonomously work with total freedom. Yet in reality it gives their employer the legal ability to assign tasks that could never get done with an equitably defined number of hours or pay, or to use familiarity to guilt them into not taking more days off than their co-workers. By giving optional days off instead of contractually honored mandated ones, the employer maintains the right to claim an employee is “not getting their work done” due to time off. And by creating an atmosphere of comparative time-off between employees, companies are able to use guilt to push longer work weeks as a way to “make up” for time off, which they supposedly are allowed to take without consequence. Some studies have even suggested that as a result of this, those with Unlimited PTO™ may actually take less days off on average than those with traditional guaranteed vacation days.

These methods together so effectively destroy the private-work divide and push the mentality of the job as a personal project, rather than a means of income. Under the guise of Do What You Love™ capitalism, false freedoms are used to convince employees that their job is a personal project, and that they should love it, rather than treat it as a traditional nine-to-five. All of this works to benefit the company and investors. And it’s important to note who is specifically targeted by this campaign of freedom and loving your work: young people. They are the easiest to sell to because they mostly have no idea what they “love” yet, pop out of college, and look for guidance they no longer have from an institution. They feel they are somehow failing by not having something they love that can make them money (that somehow doesn’t feel like labor)⁵ and the idea of working just to pay bills, like most people do, is made to be some sort of classist failure after gaining a Bachelor’s degree. In many ways tech companies operate like cults, entering campuses to recruit young people looking for easy answers for their futures and providing them with social structures and promoting dependence by cooking their meals every day or offering free beer. Coincidentally, breakfast is served early, and dinner served late, so I guess workers will just have to hang around the office for a few extra hours.

And from these overly familiar structures and loose boundaries come the additional responsibilities shifted mostly onto Project Managers and HR workers. Many PM’s become therapists to their teams—including upper management. Those of femme identities get the worst of this due to systematic misogyny, because they’re both seen as emotional-stress garbage disposals as well as sub-class workers. And for non-binary folks—my god, I don’t even know where to start with misgendering and having the responsibility intrinsically hoisted upon you to correct boilerplate contract pronouns and company emails to read properly. I cannot tell you the number of bosses who have decided to share all their anxieties with me as if it were part of my job description—and the problem is, it technically was, because their state of mental well-being was “required to get the project done.”And from this stems the beautiful secondary industry spurred by Tech™ culture…

Mindfulness-Wellness™ Sub-Economy

To dive into this, I want to start with something I experienced recently. I was with at dinner some folks who worked in tech & consulting. As it got darker outside, they all proceeded to put on orange safety glasses, which “block out blue light in order to prepare one for sleep more properly.” They all had read books on sleep techniques, many of which also purchased rings that track their sleep motion & heart rates every night to look for trends and determine their stress levels. Some of them also told me they like Mindfulness™ apps that reminded them every once in a while to stand up, pause, and do a breathing exercise via a smart watch notification. As far as they explained, this stuff helped them a lot, and I don’t intend to devalue their work, but it’s nagged at the back of my head a great deal because I felt each person was putting so much personal pressure on themselves to “fix” these problems with their bodies. They told me that if I had sleeping problems, I would understand, and yet I couldn’t help but think that I really just needed another tech/finance job to understand—because I had been in a similar position before.

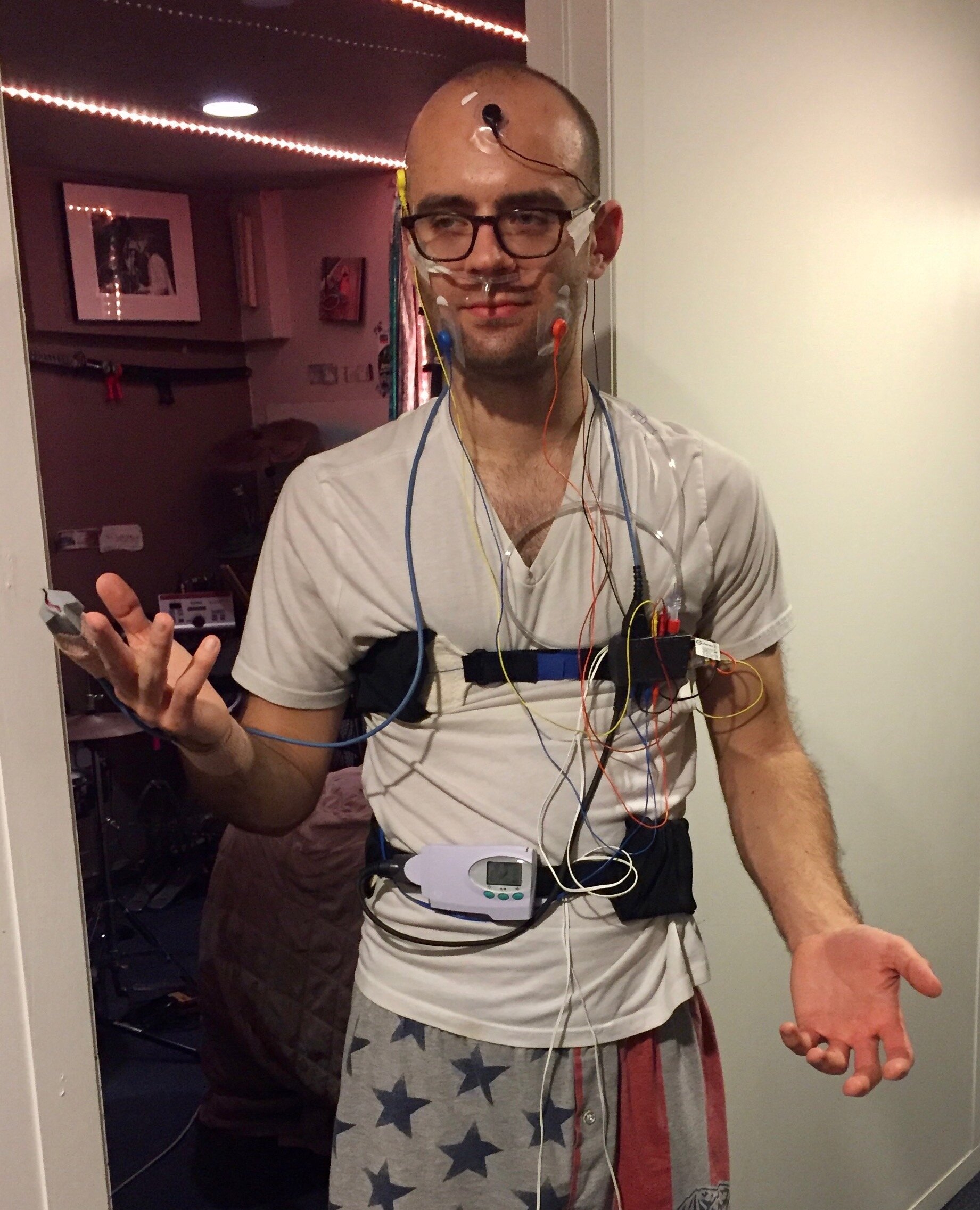

Me taking an at-home sleep test at startup cracking-point. Must have been some sort of nasal issue, maybe I watched TV too late before bed? Yeah, that must be it, startups are so cool and exciting.

I recall being in such a state of distress over my own company at one point that I experienced constant night-terrors—even going to a doctor to get a sleep test. I felt lightheaded half the days, and was having panic attacks while driving, afraid I might lose consciousness. I was in complete denial—blaming it on nasal issues, coffee, & too much screen-time before bed—and didn’t realize how much a problem there was in my life until seeing friends in the industry faint in public from pure stress and exhaustion, only to in turn blame our sleep, screen-time, & caffeine intake. What bothers me so much about this is—well primarily, that I hate to see my friends struggling—but that instead of investigating job stress, they had turned to more tech in order to cope with it. And in doing so they had paid these companies money to “fix” them, as if they had the problem, and not the work itself. That being said, can’t say I really feel that bad for them, given they make bank to be that stressed, and most of the world’s workforce is even more stressed out without making a fraction of their income. I don’t mean to devalue or minimize the sleep problems they undoubtedly have, but I do mean to interrogate how they’ve been societally trained to go about assigning blame & remedying problems. More problematic situations arise to me when mindfulness seminars and apps start to propagate inside companies themselves—a common occurrence I saw taking place in co-working space and companies I worked with.

Mindfulness and wellness programs have become a way of blaming the employee for their unhappiness instead of addressing the labor issues creating this conflict.⁶ Part of this self-tracked data being then used to power mindfulness training and fuel industries claiming to fix sleep, focus, etc. without just saying that the shit itself stresses you. While jobs teach you to be brutally efficient, waste no time, drink Soylent (literally named after a dystopic product made from the bodies of dead laborers ) to get your proper nutrition in ASAP—all in the name of loving being this unstoppable machine of suffering Silicon Valley is so obsessed with. And I am saying that as someone that actually drank Soylent daily for months. But despite all this, you’re supposed to somehow believe that a company which actively benefits from your stress is truly trying to eliminate it for you.

The insidious capitalist beauty of the tech economy stems from its ability to profit from the psychological exploitation of its own workforce. It trains progressively more “efficient” laborers by tricking them into working longer hours via delusions of personal choice—thereby increasing their stress levels while offloading blame onto the laborer’s own ability to manage mental health. Meanwhile, they sell the workers expensive products to track & remedy their stress, imparting an image of benevolence while generating a sense of status and wealth due to the marketing of the device. They then use the sellable-data & capital they collect from users to set higher expected standards of efficiency and mental “responsibility” in the industry by hooking users & companies on the service’s perceived value, allowing them to develop new products, and begin the cycle anew.

And the real kicker to all this is that all this self-tracked data users collect can be sold & used to generate further capital & products for companies (with no profit from this data going to the user), which Karen Dewart McEwen brilliantly calls (Re)productive Labor.⁷ Self-tracking generates value and simultaneously reproduces it. Apple uses its Health data for this same purpose, as well as most fitness trackers. And those in the delivery & transit gig economies are constantly contributing their data—like all my deliveries made for Uber. We believe this to be a worthy sacrifice because it is seemingly passive and allows us to use “free” services like Google Maps and social media platforms, but it is also the means by which our labor is extracted for free. And while my time delivering packages was wildly extractive and exploitative, and I certainly created more value than I was compensated for, I think the most unsustainable and unreliable income I’ve ever had actually came from my work as a remote freelancer on gig sites.

The Creative™

In my eyes the ultimate extraction of labor via emotional manipulation lies in the development of The Creative as a job title. Developed as a syntactical means to build emotional investment and make analysis of tangible actual labor impossible, “creative” workers are exploited in some of the most complex ways imaginable. The are separated from other gig workers via mainly a narrative of classism despite facing extremely similar issues of mistreatment. By calling their work “creative” the industry has managed to promote a class superiority of designers & producers over other gig workers, while simultaneously devaluing their actual labor through labeling their work as intangible and intrinsically tied to emotionality & creativity.⁸

And ad from one of the many Fiverr campaigns that has drawn intense criticism from freelancers and tech journalists.

Tech has managed to price gouge and create massive economic disparities within the freelance world due to rating & review systems. The structures of sites like UpWork, for example, basically create a system where the freelancers with the most reviews get the most work, and can charge higher rates based on their higher reviews and job-completion numbers. This means that getting your first gig is insanely difficult, meaning that one basically has to undercut the normal rate massively to get someone to take a chance on them. This causes the freelancers in the mid-tiers to lose out via massive price differences, and new workers to get paid incredibly little for their work (only to hopefully join the ranks of the exploited middle tier later). You find yourself sending out tons of proposals for listed jobs and rarely getting requests to apply. The worst part of this is that the service will charge you $10 per month if you want to be able to apply to more jobs and see other bids on projects. They make you pay them so that you can then undercut the market with the info they provide—which is straight-up devious. Because of all this, places like UpWork are dominated in large part by workers in eastern Europe and southeast Asia. Over the years I’ve worked with dozens of Ukrainian designers and developers through sites like this, or more developer specific ones like Toptal (who screen their talent), who even at undercutting rates are making what they find to be good money in terms of local spending-power. Because of this the sites (uncomfortably) represent U.S. developers as a sort of premium-feature. These gig sites are advertised as spaces to make a career, when in reality offering most people small side-jobs to supplement other earnings.

One New Yorker famously went around tagging every Fiverr ad they could find on the Subway with labor rights commentary.

However the most famously hated company in this sector is Fiverr, who’s ad campaigns⁹ are infamously cringe-worthy, especially given that the site was created as a place to pay people five dollars to do small tasks—and then spun into a full time freelancing platform. These ads attempt to capitalize on all the sorts of “freedom” and proud-suffering mentalities I’ve discussed throughout the piece. The popularization of these ideas in tech and marketing cultures is pretty clearly shown in these ads, which to anyone not deeply involved within this sphere would probably see as being pretty awful. “Nothing like a safe, reliable paycheck. To crush your soul,” one reads. I don’t think I even need to explain how out-of-touch that is.

Services like Spotify have also acquired gig services in order to aid in reproduction of the products they serve up. Their site SoundBetter takes commission from connecting music industry talent to clients in a stated goal to make your music, well, sound better. This is advertised as a benevolent gesture to get more jobs to producers and allow more openness in the hxstorically closed-off music market. But what it really does it help them to curate quality and make more content hit the platform faster—taking even more of a cut from creators who creators who make around $0.60 per thousand streams on their platform.

“Opening up” a closed-off industry does not necessarily mean improving labor conditions. That is the trick of neoliberalism in the gig-world. Who are we opening to? And are we okay with outsourcing exploitatively? And creating “gig” jobs in places with sparse job markets does create work, but if it’s not enough to truly support workers, it is only comparatively positive without actually addressing labor issues.¹⁰ The problem with the gig economy is that it’s sold as a choice without really being one. If people want to torture themselves and make extra money, go for it—but the problem is that most people are forced to do gig work just to pay rent in the gig economy. And by making “gig” the prominent syntax, which emphasizes temporality, we make it possible for people to look at full-time Uber drivers, for example, as “gig” workers when in reality that “gig” is their full time job.

Conclusions: What Now?

So where does all this leave us? We have a series of exploitative practices driving an economy of unstable jobs combined with a massive disparity in wealth and lack of unified labor front. But there are so many common issues that need to be regulated in order to protect labor rights and stop the normalization of exploitative practices in upper management that can then be reproduced further down the line on gig level jobs. We need to break up monopolies that fuel the risky economic practices of the startup world and regulate investor’s abilities to skirt conflict of interest laws in their portfolios. Minimum wages need to be applied more widely to gig workers, making their income stabile and giving them a true choice in their labor, and practices like Unlimited Paid Time Off need to be reigned in with more specific protections for required leave days. We also need to work to make much more visible the labor of “ghost workers” and freelancers that power the economy, especially from overseas, and promote the unionization of more workers in creative & freelance spaces. We need to socially combat the fetishized idea of suffering and “bootstrapping” that are mobilized to control workers and create a sense of acceptance around the financial exploitation of underpaid gig workers. We need to start treating stress as a condition brought on by exploitative corporate practices and stop blaming people’s own mental faculties. And please, we have to stop with these concepts of “families” at work. As the tech industry only grows more and more dominant, the need to understand its psychological workings becomes increasingly critical in defending the rights of workers. We must understand how tech culture creates toxic forms of capitalist exploitation and move rapidly to regulate practices and improve conditions. What we have right now does not work, it is unsustainable, and if we don’t reign it in soon the conditions of the workforce will only further decrease.

References

Wilson, J. (2015, August 18). Being Edgy and Cool Doesn't Make Tech Companies Any Less Exploitative. The Guardian.

Khan, F. (2018, December 10). The Hidden Risk in the Startup Economy. VentureBeat.

Herrera, T. (2018, August 13). Your Workplace Isn't Your Family (and That's O.K.!). The New York Times.

James, G. (2019, May 6). Scam of the Century: Unlimited Paid Vacation. Inc.

Tokumitsu, M. (2014, December 1). In the Name of Love. Jacobin Mag.

O'Brien, H. (2019, July 17). How mindfulness privatised a social problem. New Statesman America.

McEwen, K. D. (2017, September 1). Self-Tracking Practices and Digital (Re)productive Labour. Philosophy and Technology.

Voynovskaya, N. (2019, May 24). Why Do Employers Lowball Creatives? A New Study Has Answers. KQED.

Osborne, T. (2018, June 17). Why are the Fiverr Ads So Annoying? Medium.

Hatcher, J., & Tu, T. L. N. (2017, October 26). "Make What You Love": Homework, the Handmade, and the Precarity of the Maker Movement. Women's Studies Quarterly.