This Is America?

This Is America?

Mashing Up Folk-Rap to Question Cultural Boundaries & Hxstorical Biases

“Songs of survival, family love, hometown pride, imprisonment, and god.”

Mashup as Sonic Ethnography: A Background

The “mashup” exists as a strange entity in the words of popular music & ethnographic scholarship. Aside from a few examples deemed “critically-worthy” the public has generally regarded them as sort of party-tricks—not quite qualifying as electronic music like a remix, nor as its own form of sample-based production. And academics, despite their love of collections of longform, spliced up field-recordings, have generally seen them as being too modulated to be considered records of hxstory & experience. My work has sat in the middle of this confusion for about four years now.

In order to understand the project I’ll be presenting in this piece, I’d like to quickly give some background on the technique of “mashups” as cultural ethnographies. Throughout the early 2000s, seminal artists like Girl Talk & The Avalanches released some of the most insane sonic collages of the modern era and impressively captured cultural atmospheres and snapshots in musical time unlike any other artists had before. While sample-based art was not new, going back to Steve Reich’s room-scale tape loops, it had never been done in such expansive & actually listenable & danceable “mainstreamed” formats. I began producing and releasing "mashups in 2015 as Terrible, drawing inspiration from these artists. Over the past four years, I’ve released four of these albums totalling to about 950 different audio sources, 178 minutes of music, being created with about 20 months of work. This included Bike Barista Bullshit, Going Van Gogh, and Alpha Nail. The best example of this ethnographic method however is definitely found in Masshole which was a collaborative project with local blogs in Boston that essentially created a snapshot of the local scene in 2016. Only music released within the past year or so were allowed into the project.

The core concept was to try and put together as wide of a survey as possible of artists from all over in order to analyze possible intersections one might miss from simply reading about artists, or by stepping through a curated playlist. It also acted as an impetus to engage artists with each other and build connections around sharing stems, ideas, etc. It was my first attempt at really focused endeavor as opposed to a random smattering of stream-of-conciousness connections like I’d done on my other albums. It was was a fascinating challenge—and frankly just a blast to make and share with the artists who contributed.

This project as well as my other general sampling work acted as a critical praxis background for This Is America? which utilizes a similar ethnographic concept in new and much more expansive ways. The main difference—or improvement, I think—being a focus on critically examining lyrical and cultural concepts that simply didn’t take enough precedence in Masshole. While that project aimed to create a sort of locally & temporally bounded site of interaction, this newer one took aim at far more abstracted concepts of “American” identity. This is America? doesn’t simply give context, it asks questions—and that is what makes it an effective piece.

Mojave, CA

“Subie” the Subaru

Over the course of the past couple years I spent about four months driving across the country living in my 04’ Outback uncreatively named Subie. I’ve been to 44 states and 36 National Parks at this point. I listened to a massive amount of music along the way while experience the wildly varied landscapes of this massive country. I passed through arid deserts, snow-capped mountains, rural farms, post-industry cities, and sprawling megalopolises. And in turn through vastly disparate cultural, social, and economic regions. Right now In America there are a lot of narratives of division across identity—and I hoped to maybe gain a better understanding of these divisions as I traveled around. Frankly, I’m still very confused because the honest truth is that much of these divides are completely illogical and follow no visible patterns aside from highly varied classism and racism.

The biggest intersection I found so vexing was this white working class narrative of “bootstrapping” with no acknowledgement of criminal activity from ancestral generations. I’d meet white men living on welfare as migrant laborers who would tell me about how immigrants and people of color were lazy for using welfare. I’d meet people who didn’t believe in climate change as their crops died from drought, and I’d meet their neighbors who believed in the biblical apocalypse. I heard the word “race war” thrown around quite a bit—and yet also government overthrow. I met a guy in Alaska who loved the black panthers but voted for Trump. It’s a wild country. I kept remember all these discussions of people who’s great grandfathers participated in all sorts of criminal activity, and then I’d hear folk music describing this, and then I’d hear modern rap music describing so many similar stories—and I would just get so confused. In this project, I chose to explore this relationship that kept making itself clear as I listened. Musical comparisons between folk and rap do a few things: 1) They help to illuminate common hxstoric economic and social struggles while clarifying the role of systematic racism in obfuscating cultural relationships 2) They help to challenge the archival narratives of whiteness in folk music traditions 3) They sound cool.

My Google Maps account

The structure, topicality, and sounds of folk music seemed to start blending with that of rap & hip-hop in my head more than anything else. One day I’d be passing through rural trailer towns, and the next through compacted city housing projects. The lyrics & structures of the songs I’d listen to started to get totally mixed up between settings, and the sonic qualities of the tracks seemed to parallel one another after a while.

Songs of survival, family love, hometown pride, imprisonment, and god—they weren’t all that far apart in so many themes. The repetitive looping of one base, with solos sprouting off on banjos in one, and in the format of freestyling and feature verses on the other. The communal aspects of groups trading verses, trading solos, and returning to the main hooks in between. Floating Verses appeared lyrically throughout different folks’ songs just as much as they did from one rap verse to another—and appeared melodically as well through riffs and samples. Stories that played out in words throughout an entire song, without any repeating verses, and accessible vocal stylings that anyone could join in on. There was so much in common, and I’d never seriously considered it.

Marfa, TX

Before getting into the breakdown of what you’ll hear, I‘d like to critically discuss the social implications that spurred me to take further interest in this project. Urban Black Americans and Rural White Americans were in so many places I visited being faced with a slew of the exact same economic problems, and yet they existed on opposite sides of a political binary. It’s a reality that I spend a lot of time thinking about, because it’s just such a massively complex system of intersectional issues. The music I’ve explored shows so much similarity on these tangible topics, and yet remains divided based almost solely on race (which is fair considering the sheer amount of racism & systematic oppression in much of these rural areas I was in). But I want to focus on the music to see what we can start to understand as a social hxstory. That being said, I do not intend this to be a “we’re all actually the same and all struggle!” bullshit neoliberal universalist Crash narrative—it’s not. I’ll repeat because I think certain people tend to try and spin any form of cultural cross-pollination study into a success of The American Dream™, this is not your “unity” narrative of “melting pot” culture—it is explicitly meant to represent the hypocrisy in modern American cultural divides, illuminate nefariously obfuscated narratives, and use cultural overlap to contextualize the importance of experiential difference. Musicians of color in this country had the least opportunity to become artists in control of their creations, and the highest vulnerability to appropriation for financial gain from white artists and labels–full stop. These shared experiences give us a chance to investigate the real engines of division in America: racism & economic oppression.

North Cascades, WA

The issue is, ending analysis there achieves nothing in the modern movement for equality, uncovering more accurate depictions of cultural hxstory, and understanding how to improve existing systems, which is why I intend to investigate further. I hope to generate ideas via this project on ways in which conversation can better occur between seemingly disparate parties in America. The slew of economic hurdles that poor rural white and poor urban black Americans face are shockingly similar, but despite this are being used to strengthen racial divides, and I believe finding cultural similarities can help spur discussions that may help reduce the power in “othering” from a distance that maintains these apparent divides. Now that being said, “common ground” is an effective tool for communicating and learning from each other’s differences in order to progress relations, but it should absolutely never be used to negate the experiences of either party by making them universal. Because when we do that, it’s never equal, as white America always gets the benefits.

Mobile, AL

I decided to use the best tool I know of to compare and draw connections between these musical styles: mashups. And what I found began to surprise me, because while I began to find the connections between majority black rap and seemingly “white” traditions of folk music I was looking for, I also started to notice how strongly the massive base of black folk music contributed to modern hip hop stylings, and even how first nations’ musical traditions did so as well. This brought me to look further into the divisions between these apparently white and black stylings and recordings as a whole—which tends to devolve into a rabbit hole of arbitrary white music industry genre-labeling. While early white musicologists truly decided what they believed musical “roots” were, I hope to help provide some content here that might call the rigidity & accuracy of these apparent origins and connections in question.

Grand Teton, Wyoming

That being said, I think it’s important to clearly state here that this is in no way some sort of thesis claiming origins of rap music—it’s simply a thought experiment, or a series of neural connections aimed to push one to think more deeply on all the commonality between seemingly disparate genres and social groups. It’s a first attempt at a complex project that pushes some engaging and strange relationships in American cultural hxstory. It is also simply a more accessible way to consume a very large collection of music and culture at a rapid rate. But it is also in no way some sort of objective cataloging activity, as my own personal musical stylings inevitably take a large part in curating the aesthetic & tone of the piece. That being said, I tried to do my best to find middle grounds between styles I was combining as best I could.

Now that we’ve gotten that on the table, let’s get into a breakdown of the piece. I hope you enjoy it:

Sample Breakdown

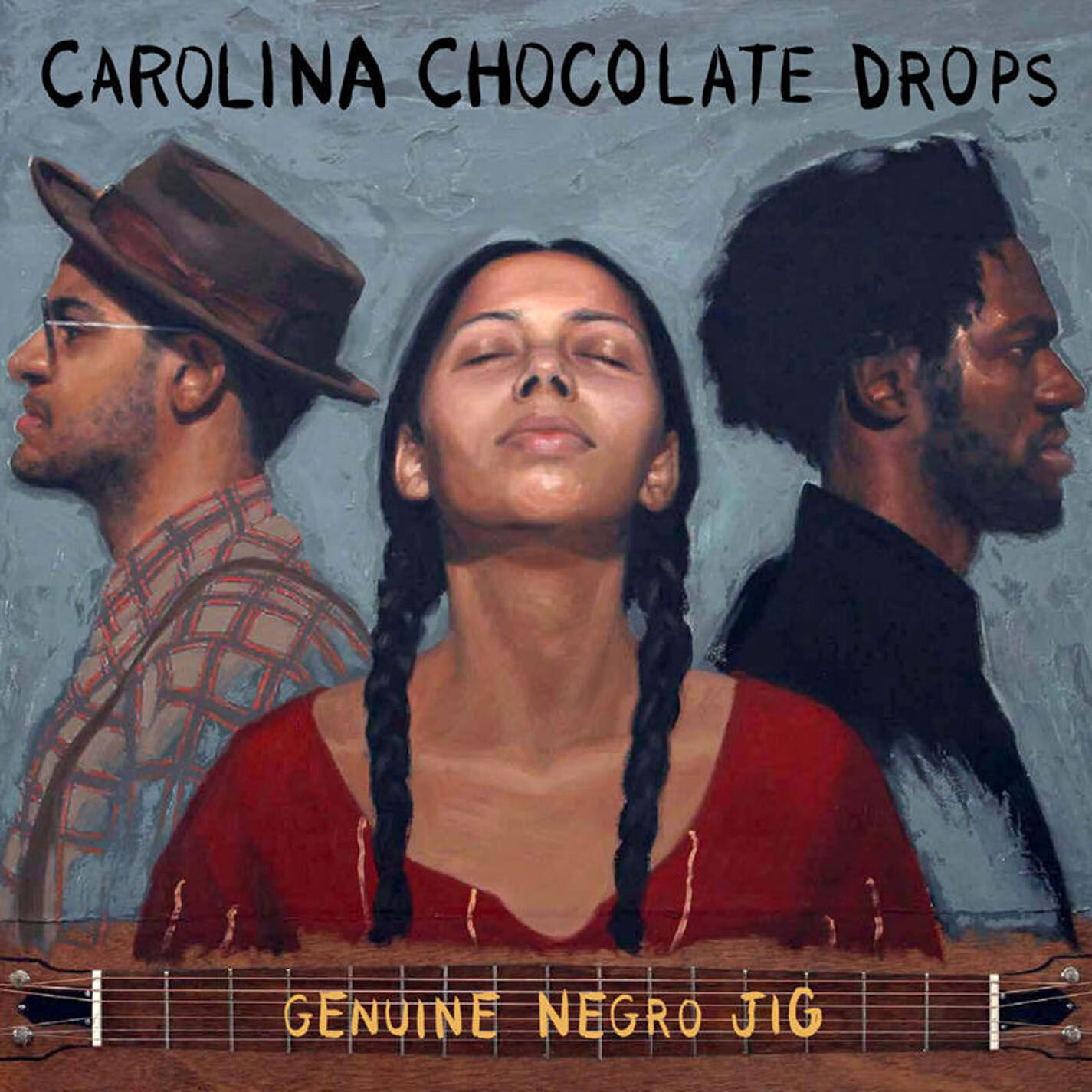

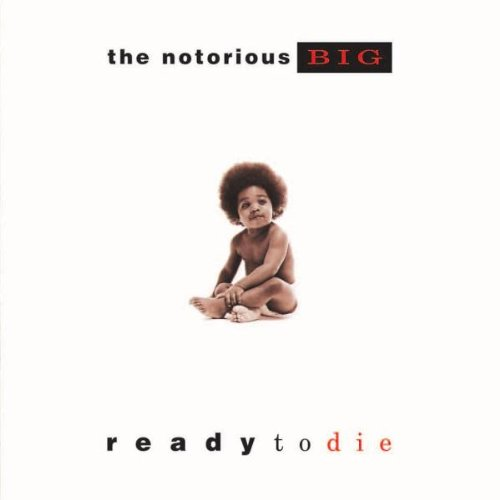

We start off hearing the beat from “Snowden’s Jig (Genuine Negro Jig)” by the Carolina Chocolate Drops. Then the first vocals we hear are Almeda Riddle singing “Jesse James” (a Lomax field recording) directly juxtaposed with the Notorious B.I.G.’s “Intro” track from Ready to Die. These two Americans seemingly couldn’t be further apart both culturally and geographically, but here we are listening to two re-tellings of a criminal—both of which do it to survive and decide to rob trains. Hearing these next to each other—one of which is lauded as a cinematic old west heist, and the other as a modern act of “gang terror”—seems to reveal some serious double-standards in the way Americans view crime. When it’s white people in the past, it’s gritty, and when it’s people of color in the present, it’s ammo used to promote “stronger” policing and critique of black youths. Over top of all of this, accenting the section, we hear Mark O’Connor’s live fiddle solo from his rendition of “Bonaparte’s Retreat” at the 1992 Merlefest.

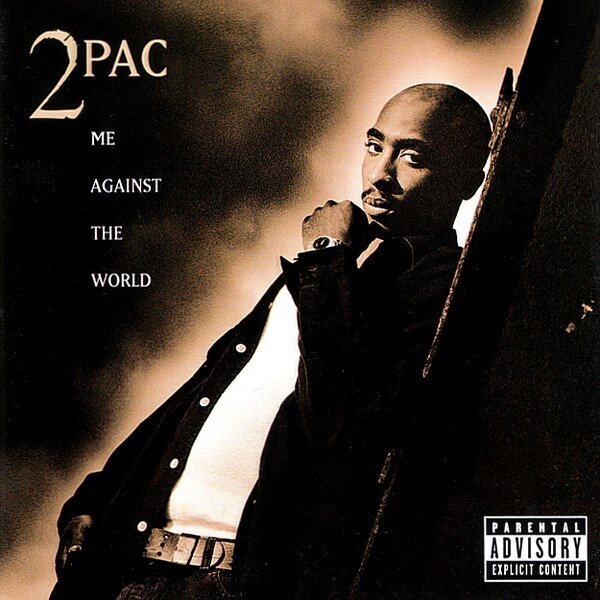

We flow directly next into a combination of Flatt & Scruggs’ “The Story of Bonnie and Clyde” and 2pac’s “Me & My Girlfriend.” 2pac refers to them as a modern version of the legendary due saying “’96 Bonnie & Clyde” as Flatt & Scruggs sings the neat-mythological tale of them. Again, we see a double standard of portrayals here: Bonnie & Clyde are a wonderous duo (these two killed a ton of innocent people and cops) to sing of, but when 2pac invokes this image to praise the intimate relationship he has with his partner, he’s viewed by the public as a “gangster rapper” which is for some reason not cool like a “old gangster movie.” Newsflash to all multi-generation white people in America: some of your relatives committed a ton of crime to get ahead (my Rustbelt relatives certainly did).

This is followed directly by a layering of 2pac’s “Dear mama” with Merle Haggard’s “Mama Tried” for topical similarities. This shifts us away from the crime narrative, and into that of family relationships and childhood upbringing. They’re both discussing complex relationships with their mothers, in which their maternal figures tried to sway them away from a dangerous life, but they simply couldn’t listen for their own reasons. It’s a similar story of both respect and rejection that involves living with one’s decisions as an adult and the parental understanding that comes with age.

Nas discusses a similar topic of youth incarceration and its effects on mothers in “One Love” after this over Bob Dylan’s version of “Gotta Travel On.” Bill Monroe then discusses a brother, Johnny, not being able to come home after spending too much time in prison in his version of the same song. Here we see similar discussions of friends & family being imprisoned and unable to re-enter normal life. We immediately next her Run the Jewels’ “Lie, Cheat, Steal” provide a back for Bill Monroe’s more trap-esque voice hitting the chorus. Sam Cooke’s “Chain Gang” provides the vocal emotes as a direct reference to Johnny’s time on the chain gang.

This leads us next into a combination of Lead Belly’s “Bourgeois Blues” and N.W.A.’s “Fuck tha Police.” Both exist as protest songs against white state oppression, and with just a tiny bit of editing, we can imagine what Ice Cube’s lyrics would have sounded like if recorded much earlier in hxstory. If Lead Belly had been making music later, or with more freedom, maybe he would have written very similar verses? The story of Bourgeois Blues is also rife with claims of coercion from Lead Belly’s label and the Lomax family, so it’s easy to imagine he may have wanted to write different lyrics.

Which brings us now to my personal favorite section. In combining Childish Gambino’s “This is America” with The Fisk Jubilee Singers’ “I Couldn’t Hear Nobody Pray” we’re able to clearly hear a maintained level of violent struggle for Black survival in America over the course of more than a century. If you are familiar with Gambino’s song and accompanying music video, you know it deals with the onslaught of threats Black Americans must face every day in this country via gun violence and systematic racial oppression. Meanwhile Jubilee is singing a spiritual discussion a lack of prayer, and a feeling of isolation and suffering. It is a song used to create community and get through times of hopelessness. Part of the way through this mashup, Northern Wind’s “Straight Up” joins the struggle, as simultaneously the American Indian/Native American populations of the continent were being forcibly moved & oppressed in genocidal practices. In the very background, we can also hear the Old Regular Baptists sing “I Am A Poor Pilgrim of Sorrow.” I included this as well to show a poor rural white perspective living at the same time in the very same country, singing a spiritual-esque song about pushing through economic hardships rural “pilgrim” life. This collection of songs serves to show a wide-ranging narrative of similar songwriting across the continent over the course of more than a century of recordings.

We lead directly into a beat using Frank Fairfield’s version of “Nine Pound Hammer” with yodeling from Jimmie Rodger’s “Blue Yodel #1 (T For Texas)” and some vocal accents by Bear Creek on “Gizhebs.” You can actually catch a tiny bit of Rick James’ vocals from “Superfreak” if you’re really good. This weaves together the sampling style of modern hip-hop with traditional folk banjo (played so expertly by Fairfield, really can’t suggest his albums enough), and the more pop-ish folk sound of Rodgers. Bear Creek serves to help us transition from our previous section and to remind us of the musical sounds in existence long before these other artists arrived in the region.

In our final section, we hear Ed Young & Hobart Smith perform “Joe Turner.” Smith is a white banjo player, Young is a black fife player, and they both lived in Williamsburg, Virginia. This track has special meaning to me, because it’s one of the first Lomax recordings I ever heard, and I completely fell in love with it (I strongly encourage you to listen to it). The vocals from this song actually discuss getting a gun, which I felt further connected the narratives of both folk and modern rap involving a large discussion of firearms. Future provides vocals from “Mask Off” to accompany the duo. His track originally features a flute & chorus from Tommy Butler’s “Prison Song” which is a 1978 track from an MLK musical called Selma, which you can hear briefly in here. The connection of this track to black hxstory is obvious, so I chose to take it even further and connect it all the way back to 18th century American black music traditions. After we fade out, I wanted to still include a section of Young’s vocals in which he talks about getting a gun to kill Joe Turner, the topic of the track. While the instrumental is most interesting to me, keeping this tone with the piece is important, and I wanted to include it as a break from the main track like it is originally performed maintain the talking pause where they discuss Joe Turner like in so many traditional songs. I tracked some sampled washboard sounds to provide some extra backing percussion on parts of this, and think it actually works pretty nicely as well.

At the very end is a bit of a “bonus track.” It’s a binaural field recording of the self-proclaimed “Golden Gate Ramblers” (which I believe was made up on the spot) from Golden Gate Park, San Francisco (November 13th, 2016). The title of the song is unknown but is likely a folk “standard” which I vaguely recall having some sort of possibly a woman’s name as the title. If you can identify this track, please let me know! This trio (two men, one woman I believe) was rehearsing together in the bandshell with a banjo, a guitar, and a fiddle, they said that they meet up after work some weeks to play together informally. I got this recording when doing a large-scale sampling mashup project, but never used it until now, funny how things work out. I wanted to include this since it’s the closest I’ve come to a Lomax-esque field recording, and because I had my binaural mics and sat in the center of them, it really is as close as you can get to being there. Hope you enjoy, I was blown away by this group, and the fact that they were happy to perform for me just sitting there was just one of the nicest interactions with strangers I’ve ever had.

Sample credits (in order of appearance)

Carolina Chocolate Drops “Snowden’s Jig (Genuine Negro Jig)” (2010)

Almeda Riddle “Jesse James” (1959)

Notorious B.I.G. “Intro” (1994)

Mark O’Connor “Bonaparte’s Retreat (Live Recording from Merlefest)” (1992)

2pac “Me and My Girlfriend” (1996)

Flatt & Scruggs “The Story of Bonnie and Clyde” (1968)

Merle Haggard & The Strangers “Mama Tried” (1968)

Grateful Dead “Mama Tried” (1969)

2pac “Dear Mama” (1995)

Bill Monroe “Gotta Travel On” (1958)

Bob Dylan “Gotta Travel On” (1970)

Nas “One Love” (1994)

Run the Jewels “Lie, Cheat, Steal” (2014)

Sam Cooke “Chain Gang” (1961)

Lead Belly “Bourgeois Blues” (1939)

N.W.A. “Fuck tha Police” (1988)

Childish Gambino “This is America” (2018)

The Fisk Jubilee Singers “I Couldn’t Hear Nobody Pray” (1909)

Old Regular Baptists “I Am A Poor Pilgrim of Sorrow” (1997)

Northern Wind “Straight Up” (2000)

Frank Fairfield “Nine Pound Hammer” (2009)

Rick James “Superfreak” (1981)

Jimmie Rodgers “Blue Yodel #1 (T For Texas)” (1928)

Bear Creek “Gizhebs” (2002)

Ed Young & Hobart Smith “Joe Turner” ” (1959)

Tommy Butler “Prison Song” (1978)

Future “Mask Off” (2017)

Golden Gate Ramblers (November 13th, 2016), title unknown

Album art is a photo of a weather balloon I took in southwest Texas near the town of Marfa